LIPIZZANERS – living legends

The second half of the 16th century was one of the most intriguing and exciting periods in history. Europe was shaken by peasant revolts as well as religious wars which ensued after the schism of the Church. The race for the colonies resulted in conflicts between the then naval superpowers while Central Europe was still threatened by Turkish raids. It was during this time that the story of the Lipizzaner horses began in the Karst.

The Lipica Stud Farm is the oldest continuously operating horse breeding institution in the world. It was established in 1580 by Austrian Archduke Charles, son of Emperor Ferdinand I. In 1564, the latter split the Austrian ancestral lands, which represented the core of the Habsburg Monarchy, between his three sons: archdukes Maximilian II, Ferdinand and Charles. Archduke Charles thus ruled Inner Austria which included the provinces of Styria, Carinthia and Carniola, and Austrian lands by the Adriatic Sea.

Floor plan schematic of the Karst Court Stud Farm in Lipica from 1780. The stud farm’s management constantly upgraded the facilities and managed the pastures, improving the conditions for the breeding of noble horses. (source: Kobilarna Lipica)

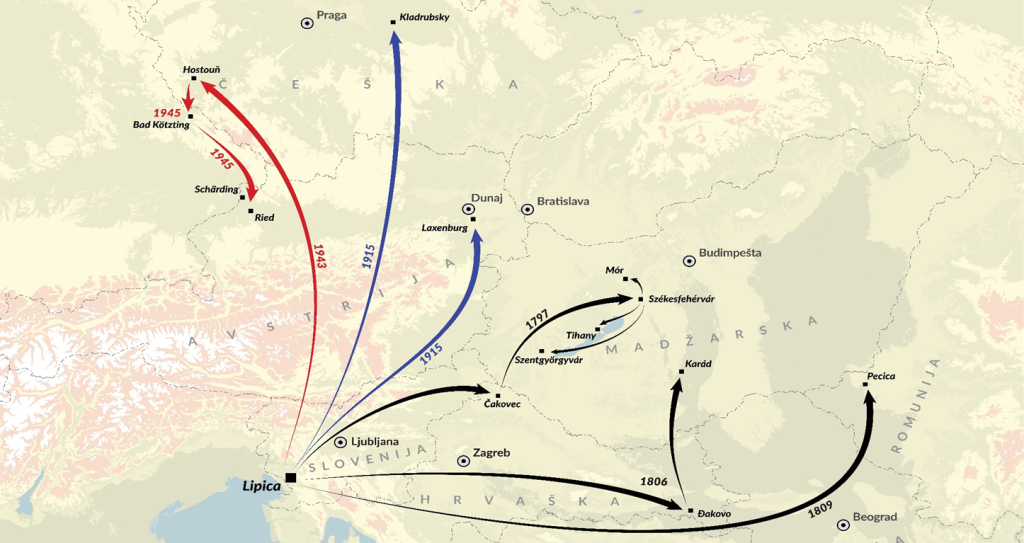

The herd in Lipica presented a great asset – Austrian rulers were aware of its importance and value, and actually treated it as royal treasure. When threatened by war, the herd thus had to be protected by all costs and in 1796, when it was endangered by Napoleon’s advancing army, the entire stud farm was relocated to the Hungarian town of Székesfehérvár, southwest of Budapest. The move presented an enormous organisational and logistical undertaking – it took the herd of almost 300 horses six weeks to travel to Hungary. After the peace treaty was signed the following year, the horses started being moved back to Lipica, with the whole herd finally being relocated as late as September 1798.

After a few years spent at home, the herd was once again on the run from the French Army in 1805. On 15 November, it set off on its way to Đakovo in the region of Slavonia where it arrived in the first days of January 1806. In October of the same year, the herd was relocated to Karád in Hungary and in April 1807, it returned to Lipica.

The Lipizzaners were forced to leave their base in Lipica many times because of various wars. No matter where they were relocated, no place offered the same horse breeding conditions as Lipica and the Lipizzaners always returned to the Karst. (author: Grega Žorž)

However, it did not stay there for long; in 1809, during Napoleon’s third advance into the interior of the then Austria, the Lipica herd was forced into exile for the third time, this time into Pecica in modern-day Romania. The move took from 12 May to 27 June 1809 and the herd remained in exile for six long years – the horses returned to Lipica as late as 1815.

What followed was a hundred years of the golden period of the Lipica Stud Farm, which came to an end on 18 May 1915 with the First World War. A few days before the Kingdom of Italy declared war on the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the management of the stud farm was given the evacuation order. The core herd, service horses and 4-year-old mares were moved to Laxenburg, south of Vienna, while the rest of the mares and all of the stallions were moved to the Kladruby Stud Farm in the Czech Republic. The end of the First World War also meant the end of the Habsburg Monarchy as well as the end of the Imperial Royal Court Stud Farm in Lipica. The newly-formed Czechoslovak Republic seized all the horses in Kladruby; the Republic of Austria and the Kingdom of Italy, which received the western part of Slovenian territory after the war – including Lipica, divided amongst them the 179 horses from Laxenburg, each receiving half of the herd. On 19 July 1919, a contingent

Horses as draught animals played an important role in supplying the army on the Isonzo Front. Borojević’s 5th Army, for example, numbered 165,561 horses in March 1917. Despite the enormous needs, the core Lipizzaner herd was untouchable. (source: Društvo soška fronta)

On 9 September 1943, the day after the capitulation of Italy, Germans marched into the Lipica Stud Farm. After only one month, on 10 October 1943, the entire stud farm or 179 horses were moved to Hostouň in the Czech Republic, which is where a lot of horses from various other stud farms ended up, including Lipizzaners from the Yugoslav state stud farms in Stančić and Krušedol, the court stud farm Demir Kapija in North Macedonia, and the Austrian Piber Federal Stud Farm as well as Arabian horses from the Yugoslav stud farm Dušanovo near Skopje and the Polish stud farm Janów Podlaski. The Nazis wanted to establish there a new centre for the breeding of Lipizzaners. Together with the herd, 14 local stable boys and the stud farm’s core archive were taken from Lipica. Six stable boys soon returned, while eight spent four years in exile with the horses.

In the spring of 1945, it became clear that the Third Reich’s days are numbered. By mid-April, the US Army had already advanced across the south of Germany all the way to the border with Czechoslovakia, which the Americans were not allowed to cross according to the agreement of the Yalta Conference.

General George Patton was an unconventional commander who had a reputation of being slightly eccentric and verbally harsh. However, he went down in military history as the general who led his 3rd Army and advanced further, liberated more territory and captured more prisoners in the given time than any other army in history. (source: US National Archives)

The noble horses in Hostouň were in grave danger as it was clear that they would soon end up in the hands of the Soviets. The experience from a few months ago was catastrophic – the Soviets used a part of the herd of noble horses from Budapest as draught animals, while they ate the rest. The stud farm’s management decided to act – they sent an informant across the border with the intention to get captured by the Americans. He was carrying a bunch of documents and pictures of these noble horses in order to attract the attention of American officers. The commander of the 2nd Cavalry Regiment of Patton’s 3rd Army, Colonel Charles Hancock Reed, immediately suggested a rescue mission. The easiest solution would have been for the Germans to bring the horses over to the American side themselves, but there were not enough of them to handle the scope of such a logistical operation. A solution was offered by General Patton, Commander of the 3rd Army of the US Military, who was fundamentally a cavalry officer and a great lover of horses. “Save them! Do it quickly!” were his legendary words. The American Army crossed the Czechoslovakian border against the stipulations of the Yalta Conference in order to bring the noble horses to the West. A unit of 70 men was supported by two tanks, two self-propelled guns and other mechanised units. On 18 April 1945, the Americans managed to capture the stud farm in Hostouň without much trouble. The rescue mission was threatened by the SS group Deutschland, which would not accept the fact that the war was lost. The Americans thus had to arm volunteers from the ranks of the rescued prisoners of war, surrendered German soldiers and Cossacks who wanted to save themselves by defecting to the West. Fighting did break out in the following days with this mixed unit managing to defend the stud farm, however, two American soldiers lost their lives in the process. The preparations for the relocation of the herd could then take place. The foals and weaker horses were loaded onto military trucks, while other horses travelled in four convoys spaced out at 30 minute intervals. In the afternoon on 16 May, the last of the horses made it safely to the Bavarian town of Kötzing.

Relocating the herd from Hostouň was an enormous logistical undertaking. The herd was split into several smaller groups, and pregnant mares and young foals were loaded onto American military trucks. (source: Ivo Mihelič, Otroci burje)

Since Eastern Austria including Vienna belonged to the occupation zone of the Red Army after the war, the Lipizzaners of the Spanish Riding School also needed to be saved. On 7 May 1945, the school’s director Alois Podhajsky organised a special show for General Patton and the command of the 3rd Army in the village of St. Martin in the north of Austria to show the general what the Lipizzaners are capable of and asked him to offer them protection and save them. Patton did not hide his enthusiasm and made a public announcement after the show, promising that the US Army would do everything in its power to protect the Lipizzaners.

General Patton was a big lover of horses and an experienced rider. Representing the United States, he even competed in the modern pentathlon at the 1912 Olympic Games in Sweden. In this photo, he is riding “Favory Africa”, one of the most famous stallions from Lipica. Adolf Hitler intended to gift this horse to Japanese Emperor Hirohito after the war. (source: US National Archives)

The Lipizzaner herd was then moved a few times around Bavaria and Austria. In 1947, the Americans handed over 109 horses with the archive and stud books to Italy as Lipica formally still belonged to Italy until the border issue was resolved. In December 1947, only 11 horses that originated directly from Lipica returned, and with tireless and dedicated work, the Lipica Stud Farm managed to establish a herd of more than 350 Lipizzaner horses. On 1 December 2022, Lipizzan horse breeding traditions have been inscribed on the UNESCO Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.

The youngest and oldest Lipizzaners are only a stone’s throw away from the Park of Military History Pivka on the Ravne estate. (author: Boštjan Kurent)

Authors: mag. Janko Boštjančič in Rok Pirjevec

Sources:

Zgodovina Lipice. Dostopno prek: https://www.lipica.org/sl/zgodovina/

Mihelič, I., (2004). Otroci burje: Lipica in lipicanec. Ljubljana: Kmečki glas

Photos:

US National Archives. Available at: https://www.archives.gov/

Mihelič, I., (2004). Otroci burje: Lipica in lipicanec. Ljubljana: Kmečki glas

Društvo soška fronta. Fotografija logistike 1. svetovne vojne

Lipicanci na paši. Author: Boštjan Kurent

Zemljevid selitve lipicanske črede. Author: Grega Žorž